- Home

- J. F. Riordan

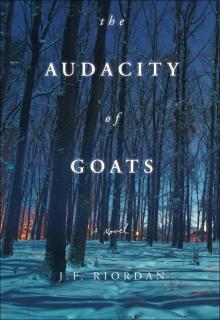

The Audacity of Goats Page 3

The Audacity of Goats Read online

Page 3

But the success of Pali’s poetry was also a source of anxiety and self-doubt. The strange experiences he and his crew had had on the ferry were closely held secrets, very difficult to keep quiet in a small community where talk was a way of life. Each man knew that their stories, if ever widely known, would make them a source of amusement and ridicule.

Pali knew what he had experienced. He knew the way the rhythms of the words had come to him. His crew knew what they had seen. Pali believed that the poetry was not entirely his own, but brought to him by the... spirit... ghost... presence... they had all witnessed on the ship. And now that he had had some success, when he was being pressed to write more by a publisher who valued his work, Pali found that he could not comply. He had no words, no phantom rhythms beating their music in his head, and no more ghostly encounters. His inspiration was gone. He was deeply troubled, embarrassed, and increasingly convinced that his glory as a poet had been a fraud. His muse—or, perhaps, his ghost—was silent, and Pali revisited daily a sense of loss and desolation in its absence.

Tonight, however, his problems seemed foolish, distant, and less important. He felt confidence and pride in his boy, and in the life he and Nika had made together. Walking into the house, he hung his coat on a peg near the door, and kissed his wife with a sense of gratitude.

After their encounter with Piggy, Fiona returned the family to the Mercantile shaken, but unhurt. She left them waving a cheerful goodbye. Abandoning bikes in the heat of Piggy battle was a scenario well-known to Mann’s employees, and Gabe took it all in stride. The parents were remarkably philosophical about their ordeal, and their good humor extended even to their children’s fright. “Things happen,” the father had said. “It’s all part of the adventure,” his wife had added. Their geniality increased when they learned that their deposit would not be forfeited, despite the bikes not having been returned.

Gabe sighed with relief when they had gone. As an Island native he had learned at his mother’s knee the rudeness and sense of entitlement of tourists, and this family had been a memorable exception. He was pleased that his only problem would be fitting all four bikes in the back of his mother’s ancient hatchback when he went to retrieve them.

Gabe’s day, however, did not go entirely as planned. He had meant to go to pick up the abandoned bicycles as soon as the store closed, planning to leave them in the car overnight and return to the store with them the next morning. But he met some friends in the parking lot as he was leaving the store, and they were going to someone’s house to hang around and shoot pool. The prospect of seeing Lara Bjornstad there put all other things out of his head. By the time he remembered, it was dark and close to his curfew. A lifetime on Washington Island left Gabe with no doubt that the bikes would still be there. He would leave early and pick them up on his way to work in the morning.

It was dusk as Ben ambled across the fields, heading home. He still had a little time before he would be expected, and he was not yet ready to be inside for the night, so he was dawdling, despite his hunger. He had a new fossil in his pocket, picked up along the beach well away from the waves, and he had seen two bald eagles fishing in the blue-gray water of the lake.

Ben knew his home territory with the intimacy that only a restless boy can have. He knew the back trails along the edge of the beaches where the ruins of the cabins of 19th-century settlers were still decaying out of sight of the main road. He had investigated them thoroughly over the years, and had scavenged small bits of metal, glass, and rusted tools. He knew where the creek went under the road and disappeared into the woods, and where it emptied into the lake. He knew where foxes and raccoons and muskrats lived, and he spent hours sitting outside their dens watching without a boy’s usual intent to harm. His affection for animals was unsentimental, and he was not offended or shocked by hunters. He recognized that killing and eating was part of life. He simply wasn’t interested in hunting. He wanted to observe, to know.

As he walked he caught a movement along the place where the field met the woods. It was the time of night when deer congregate and move out into the open fields to browse, and Ben stood still to watch. Their movement, the woods, and the low light obscured their numbers. As he peered across the distance he could see the herd of about six animals. But even in the deepening evening light it was clear that there was something different.

Cautiously, Ben moved closer. One of the animals was moving strangely, not with the usual grace of a whitetail, and it was smaller than the others. In the growing darkness and against the black of the woods, it was difficult to see clearly, but its movements were wrong: different from the movement of the other deer. Instead of a deer’s usual grace, it seemed to hobble. Was it injured? Ben peered at the distant creature. The herd seemed to notice him, and moved sharply into the depths of the woods. Ben watched, but could see nothing more. An injured deer wouldn’t last long, Ben knew. It was sad, but he also knew that there was little likelihood of being able to help the animal. It would die before spring.

Suddenly he noticed that it was darker than he had realized. The warm orange glow of the trees had deceived him, and the sun was already down. Ben ran the rest of the way home and was just in time for dinner.

He lay awake for a long time that night after he should have been asleep, wondering about the animal he had seen and feeling troubled about its fate. Nature was merciless, Ben knew, and this animal’s end would probably be a bad one.

Fiona watched the last red light of sunset from her porch steps with Rocco’s warm body lying across her feet. The mild day had turned into a brisk evening, but she could not bring herself to go in. She knew that as soon as the door closed behind her, the loneliness would begin to close in, despite Rocco’s affectionate companionship.

For most of the day she could distract herself with tasks, with only an occasional momentary longing. But at night, as the sun set and the world descended into stillness, her thoughts would drift, and with them her anxieties began their dance in her heart and head. No matter what music she played, book she read, or movie she watched, she could feel the emptiness of the house around her, and the full realization that Pete was so far away.

His presence on the Island had been so brief that it seemed as if she had imagined it. She wondered where he was, whether he could see the sky as she did now; tried to imagine what he might be doing. She knew well enough that with his job working for an international energy company, he could be literally anywhere, doing almost anything. And this made her extremely nervous. Would she see him again? Even if he wanted to, would he come back? Fiona spent a great deal of mental energy trying not to think about what could happen to Westerners in remote parts of the world.

Increasingly chilled, she sighed and stirred. She could not reasonably put off going inside any longer, she told herself, or they would find her body frozen to the steps. She stood for a moment watching the last flush of color in the autumn sky, Rocco leaning against her. Then she turned to go in, and standing aside to hold the door for Rocco, followed him into the empty house.

Ben was looking out his bedroom window down at the meadows below. There were huge numbers of turkeys gathered together, and then he realized that there weren’t just turkeys. There were... crows? Yes. Enormous crows walking on the ground. Crows ten times bigger than regular crows. As big as turkeys. And other animals. Every kind of animal. Animals that did not belong on the island. They were flowing almost as one creature below the house, simply moving in the same direction in an eerie silence. They were not interacting with one another in any discernible way, just moving. In their midst was a river of water, and strange dream animals—along with those he knew—swam along with the flow of creatures.

“Dad!” called Ben. “Come and look!” But his dad was away. He called his mom, but she was nowhere in the house. There was no one else to experience this mysterious, beautiful, and slightly alarming migration with him. No one to explain where these creatures had come from and where they were going. These creatures d

id not belong here. They should not be acting in this way. He had the uneasy feeling that something was wrong. No normal pattern would explain this behavior. He stood at the window and felt that something in the world was out of order, and he, Ben, had to make it right.

Ben awoke from his dream troubled and out of sorts. He moved slowly that morning, still feeling the after-effects of his dream, and had to be told three times to brush his teeth. He was almost late to school, and just made it into the building as the last bell rang.

When Gabe left the house the next morning, he went straight to Piggy corner, as the locals liked to call it. He knew from a lifetime’s experience exactly where the bikes would be, and as he approached he could see the gleam of the sun on the bikes’ chrome.

But when he pulled up close, it became obvious that all was not well. All four bikes were there, all right, but they were in tatters. Gabe stood by the side of the road trying to take it all in. The nylon packs that had been attached to the back of the two adult bikes had been ripped into shreds. The leather seats and the foam handle grips had been stripped away and were a complete loss.

Gabe’s common sense told him that the bikes could be repaired. The seats and grips could be replaced. But what a mess. Normally when Piggy struck, the bikes remained mostly intact, maybe with a few broken spokes, and occasionally a ruined tire. Clearly this was an escalation, no doubt the result of allowing him to get away with his bad behavior. And what a thing to happen while Tom was away, and he, Gabe, was in charge. Gabe sighed. It was fortunate, he thought, that the only damage had been to the bikes, not to the customers, but still… .

“Damn Piggy,” he thought.

Mrs. Shoesmith’s neighbor up the road was also cursing Piggy. Bill Hanson had been coming to the Island for thirty-five years, and although it was not his official residence as far as the tax man was concerned, Bill’s visits to the Island these days tended to be for twelve months of the year, more or less. He was, however, a new neighbor to the Shoesmiths, having built a house overlooking Detroit Harbor just last year. In that period of time Piggy had attacked Bill’s wife, his dog, and more out-of-town visitors than Bill could count.

The stitches, tears shed, and family turmoil that had been the result of previous Piggy encounters had been bad enough. But this. This was a bitter thing. Heartbroken, he looked upon the ruin of his baby orchard, lovingly planted young cherry and apple trees that he had nursed through the past summer’s drought and the previous winter’s vagaries. The tiny eighteen-inch saplings—representing the dreams of a lifetime—had been protected from deer by chicken wire. But chicken wire had clearly been inadequate to Piggy’s rampage. Sadly, Bill stood in the sunlight and surveyed the damage.

It was remarkable, he thought, how much destruction one small, nasty dog could wreak.

Bill was a kind husband and father, a member of the church council, and as fine and upstanding a Christian as Washington Island had ever seen. He was teased by his friends and neighbors for his gentle, upright manner, and his mild way of speaking. But some things were more than a man could bear.

“Damn that Piggy,” he said.

Chapter Two

Mike and Terry were deep in conversation one morning as they pushed open the door to Ground Zero and entered the shop, so they didn’t notice immediately the change in personnel. Instead of the beatific calm of the man Terry had come to refer to as “The Angel Joshua,” there was a singularly less angelic face scowling at them from behind the counter.

“Roger!” said Mike, suddenly looking up, possibly sensing the sharp eyes boring into his head. “You’re back.”

There was no audible response. Roger looked no different, neither tanned nor glowing with human warmth. Terry had privately expected Roger to be somehow different after his six-week honeymoon, to be changed by love. But Roger was as unsmiling as ever, his handsome face unanimated by ordinary responses, his hair sticking out at odd angles as if he had recently put both his hands in it and rubbed hard. The chill of his presence in the little shop was powerful enough to penetrate the warmth of the yellow walls, with its ambient lighting and gas fireplace surrounded by comfortable chairs.

The big Italian coffee contraption perched on the ledge behind the counter, its exotic, modern presence somehow perfectly in keeping with the bead board and rural photography on the shop walls.

“When’d you get back?” asked Terry, settling easily into the familiarity of the Roger chill. “Seems like you’ve been gone for a year.”

Roger, with long experience of their preferences, was silent as he made their coffee.

“Day before yesterday,” he said, after it had begun to seem he wouldn’t answer. “We flew into Chicago and stayed over the first night, just to get some rest. Then we got up in the dark and drove up yesterday morning. Slept all afternoon and all night, and got up at three.”

“How’s Elisabeth?” asked Mike, his sweet, cherubic face filled with his innate warmth and kindness.

“Fine,” said Roger abruptly, and he disappeared into the small kitchen in the back.

“Some things never change,” said Terry, taking a long swallow of his coffee. His eyes sparkled and he put his cup down on the counter with a thunk. Terry had never gotten used to the bland calm of The Angel Joshua’s personal atmosphere.

Joshua was, perhaps, not aware of Terry’s name for him. Terry had never been completely comfortable around Joshua. He had found Joshua’s unearthly good looks, long mane of hair, and unusual quality of benign grace a bit off-putting. The nickname, not meant in an altogether kindly fashion, had somehow struck a chord in the community. It was used by almost everyone, not as mockery, but as an expression of regard and general affection, and possibly a bit of awe. But only behind his back.

Joshua’s tenure managing the coffee shop had been a relatively brief and—to Terry—unwelcome change. After many years. Terry was accustomed to Roger’s rudeness and had come to prefer it.

“Feels good to be back to normal,” said Terry, sotto voce to Mike.

“I wonder,” said Mike quietly, looking down into his mug. Terry glanced sharply at him but said nothing as Roger emerged from the back.

“I could go for one of those egg sandwiches,” said Terry. “And more coffee.”

“The same,” said Mike, his keen eyes crinkling as he smiled. “So tell us about Italy.”

After he had started the eggs, Roger filled their cups as he spoke with unwonted animation. “We started out in Venice.”

Ben Palsson had been thinking. Would it be possible, he wondered, to find that injured deer? He could take care of it for the winter; make sure it got enough food, and then, maybe it would have enough strength to survive until spring. He knew that injuries could be self-healing. The problem would be for the animal to survive long enough for the healing to happen.

But then a new thought struck him. Maybe, if he was clever and a little bit lucky, he could figure out a way to fix its leg. He stopped his after school wandering along a wooded path as he considered this. Gradually, the idea began to grow within him, and it wasn’t long before Ben decided that he had to try. It would be fun to befriend a deer. And besides, he was worried about the little animal all alone and vulnerable, and maybe in pain.

But how, he wondered, should he start? After much thought, Ben decided that he should talk to his friend, Jim, the DNR ranger. He would have to watch what he said, because DNR people did not approve of rescuing sick animals. They always said that nature should take its course. But letting nature take its course in the death of his deer was exactly what Ben did not want. His plan was to thwart nature as thoroughly as possible, and he knew he would have to be careful not to give his plans away.

His mother had spoken often to him about sneakiness. It was something she despised. It was dishonest, she said, and showed a lack of integrity. Ben had never lied to his parents; never even felt a need to. He had an open life, and had always told them everything. But this wasn’t sneakiness, he told himself. It was a se

cret. Like a birthday party or a Christmas present. Secrets were exciting. And this one would belong to him.

The news of Lars Olafsen’s retirement was soon known everywhere on the Island. The usual morning conversation at the grocery store’s meat counter was dominated by two topics: Amand’s screamer and Lars’s retirement. The screamer was the kind of story that gave everyone a frisson of excitement. Who could it have been? What was it about? Whose kids had been allowed out so late after a reasonable curfew? Lars’s retirement, however—and its corollary: who would be his successor—were topics of far more importance.

The position of Chairman was elected by the citizens, not by the board. Usually, though, the chairman would come from the board itself. Who else would be acquainted with the requirements of the job?

To the electorate, however, the field of prospects had the unprepossessing quality familiar to anyone who has pondered future candidates for any office: they were all lacking in some key qualification. The lack of grandeur or power of the office of Board Chairman were inconsequential details; the principles were the same: People are flawed, the needs of public office manifest, and the skills required daunting. No normal human being could possibly qualify. What is more, no normal human being would want to qualify.

And so, it should have been surprising to no one when a human being whose normality was earnestly discussed wherever islanders gathered, announced her candidacy for chairman.

The first yard sign of the campaign appeared less than a week after Lars Olafsen’s announcement at Nelsen’s. The speed with which it had happened—before papers had been filed, before, in fact, Lars had even officially given notice—was a strategy intended to seek the advantage of possession of the field and to deter opposition. Predictably enough, it was in the candidate’s own front yard.

The Audacity of Goats

The Audacity of Goats